| Return to Wood of the Month Index

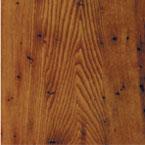

3.5 Billion Trees Lost to Fungus Chestnuts were some of the fastest-growing trees in the forest, growing at the same pace as tulip poplars. Adaptable to all kinds of soil and climate, chestnuts routinely topped out at 100 feet and in clear areas they had spreading crowns of up to 100 feet wide. Now, however, supplies of chestnut are generally scarce and expensive because of the devastation caused by chestnut blight. According to the American Chestnut Cooperators' Foundation, blight destroyed 3.5 billion American chestnuts in the first 40 years of the 20th Century. Evidence of the blight and its impact on American trees was first noted in 1904 in New York. Donald Culross Peattie, writing in the book A Natural History of Trees of Eastern and Central North America, explains: "It is believed that that blight came into this country on Chinese chestnuts (Castanea mollissima), which despite a high percentage of infection show a degree of resistance to it. No immunity existed in our American tree." In the early days when the blight was first detected, states where chestnut grew mobilized efforts to fight its spread. According to Peattie, New Jersey and Pennsylvania spent large sums of money establishing quarantine lines. Nothing worked. Foresters discovered that spores of the blight are carried by the wind, and the blight had traveled to infect all the chestnuts. Valued for Beauty and Products The species also was valued for the nuts it yielded and for the tannin found in the bark. "Native wildlife from birds to bears, squirrels to deer, depended on the tree's abundant crops of nutritious nuts," according to the American Chestnut Foundation. Chestnuts were also an important cash crop for many Appalachian families, who sent the nuts by the railroad car-fulls to New York and other major cities. Some Supplies Available The material came from a firm called Vintage Log Lumber in Renick, WV, and was purchased through Paxton Wood in Chicago, IL. "When we got the material, it had been cleaned - the paint and nails removed. When you work with reclaimed lumber, you have to be careful of nails in the wood, but most of the nails were noticeable because they left a black mark in the wood," Reistad says. Reistad says the boards varied in widths from 3 to 10 inches and lengths from 5 to 10 feet. "I pulled material for crown moulding first, taking the longest boards. For flooring we cut a herringbone pattern in random widths and tongue and grooved the material." The Comeback Effort Priorities include the development of blight-resistant American chestnuts and economical biological control measures against chestnut blight in the forest. Gary Griffin, a professor at Virginia Tech (which sponsors the ACCF Web site) writes, "It is not beyond the grasp of science to restore the American chestnut to economic importance. It could be accomplished within the next 50 years."

|

Have something to say? Share your thoughts with us in the comments below.